tech giants will stay dominant but their expansion will slow, levelling the playing field for smaller entrants

Long-awaited guidelines to regulate big tech finally emerged 8 February. Coming on the heels of the Ant Group IPO saga and the Central Economic Work Conference’s attack on ‘disorderly’ expansion of capital, they will slow the growth of tech giants over the next few years, not least in areas deemed of ‘systemic risk’. Competition by smaller platforms, SOEs (state-owned enterprises) and SMEs (small and medium-sized enterprises) will be fostered. More resources are offered for local enforcement.

tides turn against giants

The fate of tech entrepreneurs and internet giants has long been in Beijing’s hands. Despite constant tensions between the state (pursuing stability, above all) and entrepreneurs (keen to upset market equilibria), they were able to find middle ground under the banner of economic growth. Officials and well-connected investors played key mediating roles, allowing regulators to rein in tech giants only when red lines were crossed (e.g. in international counterfeiting disputes).

This consensus faltered when the stock market crashed in late 2015, reportedly convincing Xi Jinping that the private economy, championed by big tech, was losing control. Internet business, he insisted, must be held to its social and moral obligations. When SAMR (State Administration for Market Regulation) was set up in 2018, anti-monopoly was its remit. Campaigns against online gaming and news content followed. Relevant laws and regulations were amended.

Ready in 2020 to at last take on the giants, regulators put things back on hold only for the pandemic. The draft Anti-monopoly Law revision indicated the new road ahead. The presumptuous Q4 Ant Group IPO was the last straw: market, finance and cyberspace agencies all closed in.

chained to the state

Viewed through a different lens, those mediating between state and big tech lost political clout. Many were tied to the very factions that were targets of Xi's anti-corruption campaigns (Jiang Zemin-affiliated Boyu Capital, for instance, stood to benefit from an Ant Group IPO). State dalliance with big tech, including conventional regulatory capture and the ‘revolving door’ ushering former regulators into the private sector, seemed ever more a vector of systemic risk.

A very different state-market dynamic is on the drawing board, whereby firms do the state’s bidding and invest in long-term, hard R&D (like AI), bolstering industry and the real economy. Domesticating, not kneecapping (i.e. breaking up) the tech giants is in Beijing’s interest. They should have much less leeway to push back and capitalise on short-sighted gains by exploiting legal grey areas: no more stifling the rural economy with community group-buying, or predating on startups. A bounded number of firms also logistically enables more direct, centralised governance. Consistent with this, the February 2021 regulations are tangibly more lenient than the November 2020 draft.

A streamlined domestic economy is prescribed in post-COVID China; tech giants blocking startups is a no-no. Given global misgivings about big tech, this is ammunition in Beijing’s bid to play the role of ‘responsible superpower’, a responsive authoritarian sensitive to popular demand.

all eyes on regulators

The Anti-monopoly Law revision, targeting internet actors, will be fast-tracked. Executive agency strikers will be deployed rather than judicial branch goalkeepers.

Local market regulators, not SAMR, will be the primary enforcers. Their protectionist tendencies will be curbed—but not eliminated. While SAMR’s platform economy guidelines (see appendix) target exclusive dealings, predatory pricing, merger control and data abuse, its Anti-monopoly Bureau has, reports Caixin, only some 50 staff. Beijing will use a carrot-and-stick approach: a new fiscal transfer scheme for local antitrust investigations has been announced, while administrative power abuse is likely to be scrutinised. The latter will, as ever, be the last mile.

Other regulators, not least in finance and cyberspace, are to play roles, as will the judiciary. The central bank has moved to regulate financial holdings, online payment, internet finance and credit reporting; some of the regulations include antitrust provisions. In cyberspace, the Personal Information Protection Law is a priority. The judiciary has accepted ByteDance’s lawsuit challenging Tencent for blocking one of its apps on Tencent’s WeChat and QQ platforms. Litigation between JD.com and Alibaba is ongoing.

'new development era' tough talk

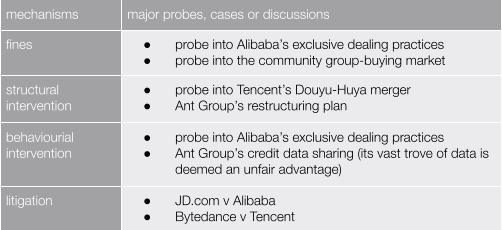

Sanctions and interventions are outlined in new guidelines on the Anti-monopoly Law (see table below), amendment of which will likely scale up financial penalties. Cultivating a handful of large and obedient tech firms, rather than handing out death-sentence fines and break-up orders, is the point. Penalties for missteps will rise from the measly C¥3 million under the Anti-unfair Competition Law, but in practice are unlikely to reach 10 percent of annual sales, the maximum under the Anti-monopoly Law. The United Front Work Department will predictably sit down with the firms and discuss warm and friendly relations.

All eyes are watching for new case precedents, likely the clearest guides to the territory in this new age of state–big tech relations. Enforcement will hailed as ‘law-based’, yet will remain frustratingly opaque given the murky industry, personal or centre-local politics.

The wild-west, clearly, is meant to see the writing on the wall. Rising on Beijing's agenda, tech giants are losing their tacit discretion. Their newly clipped wings leave them members of a 'national team' alongside the central SOEs they once challenged. This may create opportunities for smaller, more nimble firms, including international players—though they must serve Beijing's interests.

watch for

profiles

Liu Junhai 刘俊海 Renmin University Commercial Law Research Institute director

Closely involved in legislation related to corporate governance, such as the Companies Law and Securities Law, Liu as China Consumers Association vice president has long advocated stricter competition tools and enforcement. Industry policy always trumps anti-monopoly regulation in public discourse, he notes, even though the latter can promote fair competition and stimulate the market environment; both are necessary right now as China looks to build an ultra-large consumer market. Labour and consumer rights, including those related to data, must be better protected through enforceable laws and regulations, administrative measures and judicial intervention.

Guo Shuqing 郭树清 People’s Bank of China Party secretary and China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission chair

China's top financial regulator alongside Yi Gang 易纲 PBoC governor, Guo puts Xi Jinping’s ideas into action and spearheads the scrutiny of tech giants’ fintech operations. Financial innovation provides concrete benefits to the economy, such as SME access to credit, he says, but it can threaten the stability of the financial system. He makes two crucial observations that will define the challenges ahead: over 90 percent of banking transactions now occur online, and tech giants must not become too big to fail. Before taking on the fintech giants, Guo clamped down on shadow banking and P2P lending.

Xu Ke 许可 University of International Business and Economics Digital Economy and Legal Innovation Research Centre director

Long-time observer of emerging tech regulations, like data sovereignty and antitrust, Xu is often able to interpret the intent of legislators and regulators. Platforms are inevitably large given the strong network effect, he says, and the state should foster new ones to encourage competition. Regulators should focus on curbing the concentration of platform power and unfair market competition, he argues, rather than breaking them up.

context

February 2020: agency-level anti-monopoly regulations on platform economy finalised

late 2020 and early 2021: new or draft regulations on online payment, internet finance and credit reporting released to regulate fintech giants

December 2020: Central Economic Work Conference vowed to tackle monopolistic conduct and ‘disorderly’ expansion of capital

November 2020: Ant Group’s historic IPO halted

October 2020: draft Personal Information Protection Law released after years of administrative privacy campaigns

September 2020: regulations on financial holdings released to rein in firms like Ant Group

July 2020: in a landmark case, SAMR signalled internet giants, who adopted a specialised structure (see appendix), are no longer exempt from anti-monopoly regulations

throughout 2020: tech giants contributed to China’s fight against COVID-19 epidemic control

January 2020: draft Anti-monopoly Law revision released with the internet economy taking centre stage

August 2019: State Council issued guiding opinions on the platform economy, signalling what is to come

July 2019: interim regulations on monopolistic conduct announced by SAMR

throughout 2018: a series of administrative actions launched against tech giants on gaming and internet content control, ride-hailing, online education and P2P lending

August 2018: E-commerce Law announced to regulate the online market

March 2018: SAMR created in a massive ministry reshuffle; its Anti-monopoly Bureau merged related agencies previously under other central agencies; Anti-monopoly Law amendment research began

November 2017: Anti-unfair Competition Law announced to protect market participants and compliment the Anti-monopoly Law

mid 2017: Yu’e Bao, Ant Group’s money market fund, forced to introduce transaction limits as regulators grow concerned over its threat to financial stability and the state banking sector

April 2016: Xi Jinping urged internet businesses to fulfil their social and moral responsibilities

late 2015 and early 2016: high-profile stock market crash prompted Beijing to rethink internet giants and the private economy

October 2014: Surpreme People’s Court issued its decision on 360 v Tencent in its first and landmark Anti-monopoly Law ruling

August 2007: Anti-monopoly Law passed but enforcement in the internet economy was weak

appendix: the platform anti-monopoly guidelines

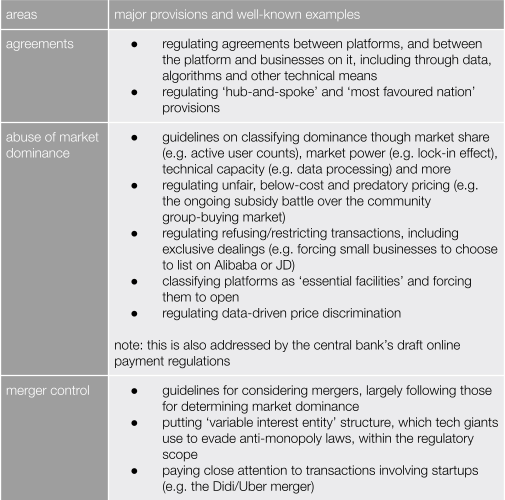

The Anti-monopoly Law is enacted by SAMR (in line with global norms) using sector-specific guidelines. It follows similar rules against big auto and big pharma. The platform economy guidelines tackle four areas of monopolistic conduct: agreements, abuse of market dominance, merger control and abuse of administrative power. The first three target enterprises, the fourth local government protectionism. Cases are running in all areas, reports Caixin.

The guidelines for platforms also help define the relevant market, a nominally (and technically) vital step in prosecution and litigation, though this is, says SAMR, implemented on a case-by-case basis.