not every foreign business need fear the cold winds of data regulation, but MNCs that capitalise on the PRC’s vast market and R&D capacity can expect to shiver

In today's ‘dual circulation’ era, global firms will have to set up two separate data systems: one to remain onshore for their PRC operations, one for the rest of the world. Regulations will come sector by sector. Activity in relation to autos and health show others what is to come.

'splinternet': two data regimes

In recent years, international industrial interests, above all those that are R&D intensive, have spoken of building at least two separate supply chains and R&D bases. Beijing’s emerging cross-border data regime provides a microcosm of its response to ‘decoupling’ from global supply chains.

Fully localise operations: this is the takeaway for MNCs (not least giants like Apple and Tesla) looking to capitalise on PRC talent and data troves. Little will change for firms that see China as only a manufacturing base or minor market. Preferential treatment may be offered at favoured sites like Hainan, but don't count on them for blanket exemptions.

Four years and a trade war after the Cybersecurity Law, Beijing is set on clarifying the rules. CAC (Cybersecurity Administration) and MPS (Ministry of Public Security) are working on criteria to sort out types, thresholds and sensitivity of important data (mainly national security, the public interest, economic order and/or state operations, see annex I).

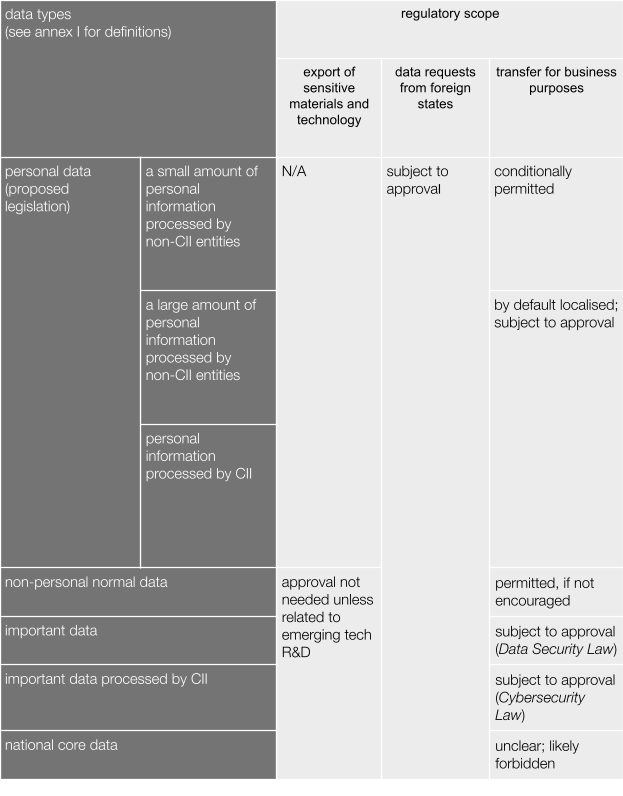

Normal data (including personal information) vital to business and trade can flow across borders. But as stipulated in the recent labyrinthine laws on cybersecurity and data security, as well as that proposed for personal information protection, data of strategic importance may not be transferred without state approval (see annexes I and II).

cross-border data transfer regulations for different types of data

autos and health: test cases

Defining the data regimes results from intense behind-the-scenes negotiations among stakeholders. The broad definition of terms, processes and categories leaves room for tailoring to sectorial and even local needs. Regulatory design will not rest with the security establishment, privacy advocates or protectionist officials: sectors or regions whose data localisation rules deter investment may win more lenient terms from central agencies and/or local governments. Greater leniency is also mooted for SMEs, sensitive to high compliance costs.

Regulatory scrutiny in the pivotal auto sector flags changes likely to become system-wide (external link). Industry regulator MIIT (Ministry of Industry and IT), in tandem with CAC, responded to Tesla’s opaque and controversial data collection practices with data security criteria. Rules are tailored to the sector: personal data collected by automakers, ride-hailing services, repair shops and insurance firms may not be sent overseas without CAC approval; non-personal data deemed of national importance, e.g. flow of traffic in military and defence sites, high-precision map data, etc., must also stay in China. Tesla, BMW and Daimler have now announced plans to store all consumer data locally. In future, one-off market entry requirements may apply to smart vehicles.

Such efforts are mirrored in the healthcare sector, where NHC (National Health Commission) has formulated data regimes. Population and healthcare data are subject to stricter rules than those prescribed by the new laws: most data, personal or not, must remain in-country. Transfer of human genetic data is strictly prohibited and separately regulated. Similar to the auto sector, smart medical equipment is governed by standalone rules.

tight regulations, loose enforcement

Restrictions on cross-border data transfer are unlikely to be rigidly enforced, given that export control rules have never been carried out with much heft. Limited capacity at the centre is one reason, not unlike General Data Protection Regulation enforcement in Europe; fears of stifling foreign R&D investment is another.

Big firms holding personal information in bulk, or whose IT footprints have a significant impact on the domestic economy, are the bogeymen. They will be (or, as in the cases of Apple and Tesla, already are) the first to be asked by regulators to store personal information and important data locally.

Sectors mooted for more stringent treatment are those in which all parties converge on the need to localise storage, e.g. healthcare and genetic resources or, even more strategically, smart vehicles and voice recognition algorithms.

Prior to passage of the Personal Information Protection Law and auxiliary regulations, international players will be reviewing their China operations and associated data flows. Once they are embroiled in controversy, or when Beijing’s bristles at some geopolitical event, it will be too late.

profiles

National Information Security Standardisation Technical Committee (TC260) 全国信息安全标准化技术委员会

Highly influential in China's cyberspace, TC260 issues scores of standards that guide both officialdom and industry. CAC in one case held local officials to a TC260 privacy standard at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The committee is led by CAC, MPS and MIIT officials; standards are often set by working groups of stakeholders, ranging from academics to tech giants. Alibaba and Huawei are particularly active in shaping industry standards. Token foreign companies are to be found in standard setting, though rarely.

Zuo Xiaodong 左晓栋 | China Information Security Research Institute vice president

What qualifies data to stay in China, advises Zuo, must be clarified as soon as possible. The 'importance' criterion by which it could be prevented from leaving, per the Cybersecurity and Data Security laws, should exclude all but critical security and public interest content. Normal flows of commercial data must not be discouraged, Zuo notes, in line with international standards.

Now steering a CAC-backed group working on criteria for important data, Zuo is a data security veteran. His doctoral worked touched on the PRC's initial strategy in this field.

He Shanshan 何姗姗 | Zhilian Transportation Research Institute autonomous driving legal director

Data security regulations should leave space for the autonomous vehicle industry to grow, argues He Shanshan, given that China is competing with other countries in this field. Regulators are inclined to grade data based on its risks, she notes. Local-level regulations should be more practical than national ones.

Expert in legal issues surrounding autonomous driving, He Shanshan is a special advisor to the Ministry of Transport, the Supreme People's Court, as well as the municipalities of Beijing, Shanghai and Changsha.

annex I: four levels of data and two levels of personal information

cross-border data transfer regulations for different types of data

four levels of data

Data is divided into four grades under the Data Security Law, coming into effect September 2021, and the Cybersecurity Law.

Normal data (i.e. day-to-day private and commercial data) can be transmitted across borders freely given its vital role in normal business and trade flows, as long as it is not subject to export control.

Note that it may also be in the interest of businesses to store their data locally, or even delete it as soon as possible. Autonomous driving experts for instance note that smart vehicles collect an extraordinary amount of data: storage or cross-border transfer on this scale is not necessary or economical.

Important data, which is yet to be legally defined but generally refers to data that has implications for national security, the public interest, economic order and/or state operations, cannot be transferred overseas without approval from cybersecurity and industry regulators. Watch for

- State Council management measures for important data outbound transfer, for which CAC will lead the drafting process

- national catalogue/standard for important data: localities and ministries will clarify their region- and sector-specific jurisdictions

- State Council regulations for implementing the Data Security Law, currently being drafted by CAC

- a national recommended standard that clarifies the scope of important data, which TC260 has been working on since 2019

Important data processed by CII (critical information infrastructure), which is also yet to be legally defined but generally refers to ‘network facilities and information systems vital to the continuous and stable operations of critical businesses’, which are in turn essential to national security, social stability, public health and economic security. Similar to important data, industry regulators are instrumental in defining what constitutes critical businesses. MPS has an internal list of CIIs, and experts close to the legislative and standard-setting processes suggest that CII does not concern most foreign enterprises. Watch for

- State Council regulations, which CAC, MIIT and MPS have been working on since at least 2017

- national recommended standard that clarifies the boundaries of CII, which TC260 has been working on since 2019

National core data is separately governed and relates to ‘national security, national economy lifeline, significant livelihood issues and major public interests’, which likely includes but is not limited to state secrets.

two levels of personal information

Personal information is divided into two levels under the Personal Information Protection Law, still in draft, and the Cybersecurity Law.

Non-CII businesses that process a small amount of personal information, according to the draft Personal Information Protection Law, can transfer it overseas as long as they obtain consent for the transfer, conduct a pre-transfer risk assessment, keep a record of all transfers, and use one of the officially sanctioned mechanisms

- undergo a CAC-sanctioned security assessment

- receive certification from CAC-sanctioned professional agencies

- follow a CAC-sanctioned standard transfer contract

- follow mechanisms outlined in other laws and regulations

Note that there is some uncertainty at the sectoral level. Apart from the law still being in draft and subject to change, it may also contradict the proposed rules on automobile data management, which may suggest all personal information collected by smart vehicles should be kept in China. Some legal scholars believe the proposed auto rules will conform to the Personal Information Protection Law once it is finalised.

CII businesses that process personal information, as well as normal businesses that process a significant amount of personal information, can only transfer personal information overseas if they undergo the CAC-sanctioned security assessment; other mechanisms are not available to them. Draft standards put the threshold for ‘significant amount’ at data of 500,000 or 1 million individuals. Watch for the final Personal Information Protection Law.

annex II: laws and regulations

A labyrinth of laws, regulations and standards indicate the direction of cross-border data transfer. The major ones, including drafts and those proposed, are as follows

- overarching legal framework

- Cybersecurity Law (effective July 2016)

- Export Control Law (effective December 2020)

- Data Security Law (effective September 2021)

- Personal Information Protection Law (second draft) (issued April 2021)

- CII rules

- Guiding opinions on implementing Cybersecurity Multi-Level Protection System and CII (issued September 2020)

- Operational guidelines for cybersecurity assessment (effective June 2016)

- Regulations on CII security protection (draft) (issued July 2017)

- Information security technology—Method of boundary identification for CII (draft) (issued August 2020)

- Guidelines on CII identification (proposed July 2017)

- cross-border transfer of data and important data identification

- Personal information and important data outbound transfer security assessment measures (draft) (issued April 2017)

- Information security technology—Guidelines for cross-border data transfer security assessment (draft) (issued May/August 2017)

- Management measures for data security (draft) (issued May 2019)

- Guidelines on important data identification (proposed August 2019)

- Regulations on data security management (proposed June 2021)

- Catalogue for important data (proposed June 2021)

- Management measures for outbound transfer of important data (proposed June 2021)

- cross-border transfer of personal information

- Information security technology—Personal information security specification (effective October 2020)

- Personal information and important data outbound transfer security assessment measures (draft) (issued April 2017)

- Personal information outbound transfer security assessment measures (draft) (issued June 2019)

- auto regulations

- Guidelines on smart and connected vehicle manufacturing enterprise and product market entry management (trial) (draft) (issued April 2021)

- Several rules on automobile data security management (draft) (issued May 2021)

- Guidelines for the development of a cybersecurity standard system for internet of vehicles (smart and connected vehicles) (draft) (issued June 2021)

- Internet of vehicles information service user information protection specification (effective October 2020)

- Internet of vehicles information service data security technology specification (effective October 2020)

- Information security technology—Connected vehicle—Security requirements for data (draft) (issued April 2021)

- Internet of vehicles data cross-border flow security management specification (proposed June 2021)

- Internet of vehicles data cross-border flow security assessment standard (proposed June 2021)

- healthcare regulations

- Management measures for population and health information (trial) (effective May 2014)

- Management measures for national health and medical big data standard, security and services (trial) (effective July 2018)

- Guiding principles on medical device cybersecurity registration and technology vetting (effective January 2018)

- Regulations on human genetic resources management (effective July 2019)

- Biosecurity Law (effective April 2021)